Introduction

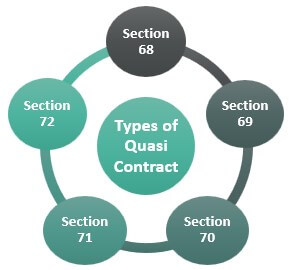

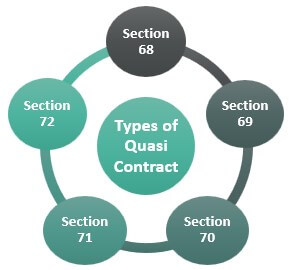

Section 68 to 72 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872 talk about “Quasi-Contracts or Certain Relationships Like Those Created by Contracts.” A contract suggested in law, also called a quasi-contract, is a relationship that looks like a contract. A consensual contract is one in which both sides agree to the terms of the deal. This one is not. The idea that these duties exist comes from the law.

The idea of “quasi-contracts” comes from the theory of “unjust enrichment.” For Example: The idea behind these agreements that look like contracts is called “Nemo debet locupletari ex aliena jactura.” It means that no one should get rich or gain something at the cost of someone else’s loss.

Theory of “Unjust Enrichment”

A general rule of law that says no one should be able to get rich off of someone else’s problems without paying back the fair value of any goods, services, or other advantages they unfairly got and kept[3]. Which means that if someone gets something good from someone else and causes that other person to lose something, the person who got the good thing must pay that person back in the same amount. Also, Black’s Law Dictionary says that unjust enrichment is when someone keeps an advantage someone else gave them without paying for it, even though someone should have paid.

Features of Quasi-Contract

The origin of a quasi-contract is not in offer and acceptance, which is an agreement between two or more parties similar to that of a contract. It is enforceable by law, but it is not created by a contract. Quasi-contracts are Right in which it indicates that a person has rights exclusively against one other person or party to the contract. According to the notion of quasi-contract, the individual who bears all expenses is entitled to obtain money or unjust enrichment. Quasi-contracts are created using legal fiction. To construct a quasi-contract, three requirements must be met:

The party bringing the lawsuit must provide any proof of the products and services for which the defendant is obligated to pay them.

It is necessary for the defendant in this case to have accepted such goods and services and to have benefited in some way from them.

Finally, the plaintiff should not have been able to obtain such goods and services due to the defendant, as the defendant must have accepted them under those unfair circumstances.

Types of Quasi-Contract

Section 68

According to Section 68, a contract or legal obligation can be formed between two people, one of whom is able to provide for all of their needs while the other is unable to do so. In this scenario, the party providing all supplies has the right to claim his share of the property belonging to the party unable to enter into a contract.

For example Kartik and Aman have been friends since they were young children, but after an accident, Kartik’s doctors have labeled him as insane. Taking charge, Aman resolves to look after his friend Kartik and his family as well. Therefore, Aman has a claim to reimbursement from Kartik’s assets.

In Nash v. Inman, it was decided that in situations where caring for a baby and providing for all necessities seems necessary, the plaintiff must demonstrate that the goods are crucial to the infant’s life and that he was not in possession of them at the time of sale or delivery. In another instance, Chappel v. Cooper, it was decided that the defendant’s baby widow needed to pay for her husband’s funeral.

Section 69

According to Section 69, a person who has an interest in paying someone else who is legally obligated to do so may reimburse that person for the whole amount he was required to pay.

For example Kartik is the only one who makes money from the land that Aman leased to him; he farms the land. Owing to Aman’s unpaid arrears, the government listed the land for sale, which would eventually cause Kartik’s rights to be revoked. Kartik made the decision to pay the money and stop the government from reselling the land. Aman now has the right to receive his money back from Kartik’s refund.

Section 70

Section 70 discusses the legal obligations that arise when someone performs a non-gratuitous act. When someone gives something not freely—perhaps by accident or out of a stated wish to regain ownership of it—and the recipient uses it for their own benefit, the giver is entitled to receive the item back, the money, or any other damages his actions may have caused.

For example When Aman gives a suit to his tailor for fitting and the tailor accidentally gives Aman’s suit to another customer, the tailor has the right to return the exact suit to Aman, the money Aman paid for it, or even the suit itself. This way, Aman won’t be left out and the tailor won’t unjustly become wealthy.

In the Mulamchand v. State of M.P. (1968) case, it was noted that it became necessary to argue that parties falling within the section 70 per se scenario do not have a contract. As a result, the party is barred from suing for damages of any sort as well as for breach of contract or particular performance of the contract. This states unequivocally that in cases requiring compensation and falling under section 70, the amount due is not contingent upon any prior contract, as there was none, but rather on a different type of duty. In this situation, the obligation’s conceptual foundation is not a contract, but rather a distinct legal type known as a quasi-contract.

Section 71

A further duty for the person who found the goods in the photo is mentioned in Section 71. Sections 151–152 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872 describe the obligations and duties of the person who finds another person’s possessions. These obligations are comparable to those of a bailee in a bailment situation. According to Section 151, the finder of goods is not liable for compensation and should treat the goods as if they were their own. For example, if someone finds a bag of money on the road and tries to keep it for themselves, but a thief attacks and takes the bag from him. In this case, the finder is not responsible for providing any compensation. According to Section 152, the finder shall not be held responsible for the loss, deterioration, or destruction of the products caused provided he has exercised all reasonable care that appears essential.

Section 72

According to Section 72, an individual is entitled to a total refund of any money that was given to them unintentionally or under duress.

For example Together, Aman and Kartik had to give Shekhar 10,000 rupees to rebuild the wall separating their homes. Following reconstruction, Kartik and Aman each paid the whole sum. Shekhar is now qualified to get the additional portion of Aman’s share that he originally paid to him back.

It was determined in Sales Tax Officer v. Kanhaiya Lai Sara that money paid in error, whether due to factual or legal error, will be recouped. The term “mistake” has no restrictions on its use under section 72. In this instance, a company complied with U.R. sales tax legislation by paying a specific amount of sales tax on its forward transactions. The Allahabad High Court declared that the sales tax imposed on these kinds of transactions was excessive after the payment. The company tried to get the tax money back. It was approved by the Supreme Court.