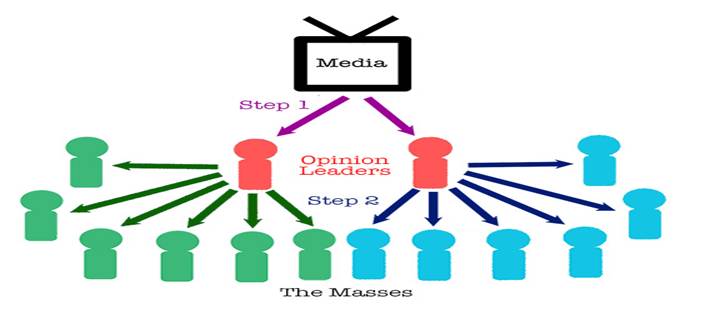

The advent of digital media and the rise of social platforms have significantly transformed the dynamics of agenda setting, usage, and gratification. Today, individuals have unprecedented access to a vast array of media sources and platforms, enabling them to curate their news consumption experiences. Social media platforms, in particular, have become powerful tools for both agenda setting and gratification fulfillment. Users can actively engage with content, participate in discussions, and share information, shaping the broader public agenda and finding gratification in the process.

Journalists, too, have adapted to this changing landscape by utilizing social media platforms to disseminate their work, engage with audiences, and gather insights into public preferences and concerns. By harnessing the power of social media, journalists can effectively set agendas by amplifying important stories, encouraging dialogue, and meeting the diverse preferences of their audience.

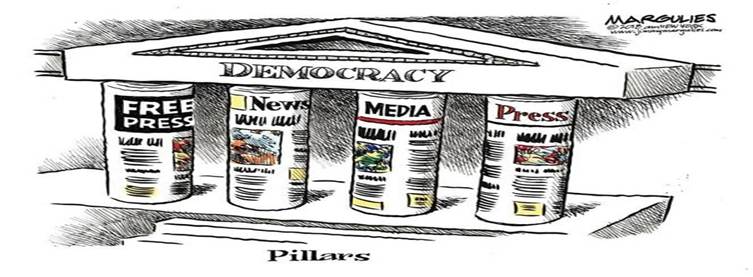

Understanding the theories of agenda setting and uses and gratifications offers useful perspectives on the dynamics of media influence and audience engagement. Aspiring journalists must grasp the role of media in shaping public discourse and the active role audiences play in seeking and consuming media content. By utilizing these theories, journalists can navigate the evolving media landscape, effectively engage with their audiences, and contribute to a media ecosystem that informs, entertains, and empowers the public. By understanding how agenda setting and gratification fulfillment work together, journalists can write stories that are important to their readers and meet their needs and wants. This creates a meaningful and mutually beneficial relationship between the media and society.

The global coverage of the George Floyd protests in

Introduction

The theory of media framing provides valuable insights into how news organizations shape public perception by emphasizing certain aspects of an event while downplaying or excluding others. The global coverage of the George Floyd protests in 2020 serves as a pertinent example that highlights the significant role of media framing in shaping public opinion and mobilizing social movements. This incident demonstrated the power of media in influencing public discourse, policy changes, and societal transformation.

1. Background

In May 2020, the tragic killing of George Floyd, an African American man, by a white police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota, sparked outrage and protests across the United States and the world. The media played a crucial role in disseminating information, amplifying the voices of protesters, and catalyzing a movement for racial justice and police reform.

2. Media Framing

Media framing involves selecting and emphasizing specific aspects of an issue or event to shape public perception and understanding. During the George Floyd protests, media framing played a pivotal role in influencing public opinion, mobilizing support, and catalyzing political and social changes. Two prominent frames emerged during the coverage: the “Protest” frame and the “Riot” frame.

3. Protest Frame

Many media outlets, particularly those sympathetic to the cause, framed the events as peaceful protests against police brutality and racial injustice. This framing highlighted the demands for justice, systemic change, and equality. News stories often featured peaceful demonstrations, poignant speeches, and interviews with activists, emphasizing the legitimacy of the movement and the urgent need for reform.

4. Riot Frame

Conversely, some media outlets, especially those seeking sensationalism or prioritizing law and order narratives, framed the protests as riots and instances of civil unrest. This framing focused on violence, property destruction, and clashes with law enforcement. News stories highlighted looting, fires, and confrontations, which reinforced negative stereotypes and detracted from the underlying message of the protests.

5. Effects of Media Framing

Media framing during the George Floyd protests had several notable effects:

- Shaping Public Opinion: The framing choices made by media organizations influenced public opinion and perception of the protests. Those exposed to the “Protest” frame were more likely to support the demands for justice and reform, while those exposed to the “Riot” frame might have had a more negative view of the movement.

- Mobilizing Social Movements: Media coverage played a vital role in mobilizing widespread support for the protests. The “Protest” frame, particularly when shared on social media, facilitated the dissemination of messages, images, and videos that resonated with individuals across the globe. This led to increased participation, solidarity, and the amplification of the movement’s goals.

- Policy Changes: The extensive media coverage and public response to the protests prompted significant policy changes. The calls for police reform, defunding, and racial justice gained momentum and led to tangible actions at the local, state, and national levels. The media framing contributed to the visibility and urgency of these demands, pushing policymakers to address systemic issues.

- Journalistic Implications: From a journalistic standpoint, the coverage of the George Floyd protests highlights several important considerations:

- Responsibility and Accuracy: Journalists have to be responsible when they choose how to frame a story, making sure that it is accurate, fair, and gives a full picture of what happened. The selection of frames should align with the principles of truth, objectivity, and the pursuit of justice.

- Media Ethics: Ethical considerations should guide journalists when reporting on sensitive and polarizing issues. Sensationalism and bias can hinder the quest for truth and understanding. Journalists should strive for balanced reporting, offering multiple perspectives and giving voice to marginalized communities.

- Media Literacy: The incident demonstrates the value of media literacy among the general public and especially among students. Media literacy empowers individuals to critically analyze news coverage, identify biases, and understand the impact of media framing on public perception. By fostering media literacy skills, journalists can contribute to a more informed and discerning society.

The way the media covered the George Floyd protests shows how important framing is in shaping public opinion, getting people to join social movements, and making changes to policies. Media organizations’ use of the Protest and Riot frames significantly influenced the public’s perception of the protests. This incident serves as a reminder of the responsibility journalists have to report on sensitive issues in a fair and accurate way. It also shows how important it is for people to be media literate so they can understand media stories. By understanding and critically analyzing media framing, students can become informed citizens who actively engage with the media and contribute to a more inclusive and just society.